Note: This article first appeared in the November 2021 edition of the Internet Law Bulletin.

Following the landmark decision in the Federal Court,1 the issue of technologically and internet-mediated creation has returned to the centre of attention. The decision is an important reminder of the legal and philosophical issues surrounding artificial intelligence (AI) that have not yet been solved.

In this article, we explore how the law can deal with AI and intermediated creation.

The first wave — the machine as a slave

The word “robot” derives from the Czech word robota “slave/corvée labour”.2 Consistently with that, the first wave of machines and robots were dumb, brute things carrying out simple commands that were written and devised by humans.

This genealogy can be traced back to at least Pascal’s calculator, Babbage’s difference engine and potentially even the more ancient abacus. The tattoo machine in Kafka’s Strafkolonie, which engraves the law presumed to be broken by the prisoner into the body of the condemned, is equally a primitive (and horrific) legal brute force machine.

A human invented the machine, and devised its controlling algorithm. At best the machine was a tool by which human invention created property.

It is clear that such machines were pure property, being a physical thing that was capable of being owned by someone (ie a person or a corporation). As a flow-on effect, anything created by it was obviously also owned by the owner.

In no way could the machine be seen as the inventor or owner of the product. The classic rules of intellectual property ownership reflect this primitive stage.

Primitive forms of AI, such as binary picture matching and QR codes, are equally part of this first wave.3

The middle position — robots creating things

We have now moved beyond the primitive first wave, and a number of decisions have grappled with the legal ramifications of what happens when robots/AI create things.4

On 31 July 2021, the Federal Court in Thaler v Cmr of Patents (Thaler) was required to consider whether an AI system could be named as an inventor for the purpose of the Patents Act 1900 (Cth) (the Act) (the decision is subject to appeal).

The Commissioner argued that an AI system could not be an inventor, arguing such a determination would be inconsistent with s 15(1) of the Act,5 mainly on the basis that the Act is “not capable of sensible operation in the situation where an inventor would be [AI] machine as it is not possible to identify a person who could be granted a patent”,6 particularly where “the Act requires a human inventor”.7

Justice Beach thought otherwise, finding that AI can be an inventor for the purposes of the Act: “We are both created and create. Why cannot our own creations also create?”8 Significantly, in terms of ownership the court held that the owner of the patent must be a person (whether natural or corporate).9

Albeit being a case about registrability in patent law, the import of the court’s to recognise AI as an inventor cannot be overlooked.

The decision reflects not only trends in other jurisdictions,10 but the inevitable.11 The decision to recognise that AI can invent is “simply recognising the reality by according [AI] the label of ‘inventor’”.12

What does this mean you may ask? How far does this go? Well, for now, the decision is only precedent for AI inventors seeking a patent application. His Honour seems to stress however, the idea that technology is controlled by society and the law.13

The decision imposes important legal and philosophical questions and concerns for some. For example, accepting AI systems as inventors has been argued to evolve the status of AI to that of a legal person, which would allow them to hold and exercise property rights. Alternatively, the decision makes a lot of commercial and, in the author’s views, theoretical sense when one considers the positive flows to innovation and research and development incentivisation. His Honour’s observa- tions concerning the reality of the evolving nature of AI inventions illustrate a reactive approach which encourages the law to become part of the process. It recognises both the inevitable and indispensable trajectory of AI in the data-drive nature of our world.14 The current trajectory requires lawyers to adopt a harmonised approach to a broader law reform and the extent to which emerging technologies should be accommodated.15

Thaler dealt with an intentional creation of AI

B2C2 Ltd v Quoine Pte Ltd16 (partially overturned on appeal — the breach of contract appeal was dismissed but appeal on breach of trust allowed: Quoine Pte Ltd v B2C2 Ltd17 (Quoine)) is usually considered in the context of contractual relationships between two persons when AI goes wrong. However, viewed from another angle it exemplifies the Sorcerer’s Apprentice or Terminator scenario18 — when AI creates things that its initial creator/programmer did not intend.

Quoine concerns a series of trades that arose out of an accident on the platform in which Quione operates a currency exchange platform. The seven trades that were affected by the platform for B2C2 were traded at “a rate approximately 250 times the . . . previous going rate”.19 Once the chief technology officer of Quione became aware of the trades, “he considered the exchange rate to be such a highly abnormal deviation from the previously going rate that the trades should be reversed”.20 Accordingly, the proceeds of the sale that had been automatically credited to B2C2 were reversed.

It is helpful to pause here and examine the position a little more closely. Because the Trading Contracts had been entered into pursuant to deterministic algorithmic programs that had acted exactly as they had been programmed to act, it is not clear what mistake can be said to have affected the formation of the contracts. The mistake, if anything, was in the way the Platform had operated as a result of Quoine’s failure to make certain necessary changes to several critical operating systems, which led to a series of steps that force-closed the Counterparties’ positions and triggered buy orders for ETH being placed on their behalf. This might conceivably be seen as a mistake as to the premise on which the buy orders were placed, but it can in no way be said to be a mistake as to the terms on which the contracts could or would be formed. If a party A is told a falsehood by B which causes A to accept C’s offer to transact at a price A would not otherwise have transacted at, in circumstances where C was neither aware of nor involved in B’s falsehood, we are unable to see how that falsehood can be said to be a mistake that vitiates the contract. Here, the problems with the Quoter Program and the subsequent force-closure of the Counterparties’ positions are akin to a “falsehood” told by Quoine to the Counterparties. This cannot be a mistake that vitiates the Trading Contracts between B2C2 and the Counterparties.21

The relevance of Quoine for the purpose of this discussion is what the “second stage machines” created. Specifically, what the AI contracting system created by accident and consequence of its actions in a commercial setting. In this case the “creators” of the creator did not intend the action, and at least one of them regretted what happened (financially anyway), but viewed from another angle Quoine illustrates the problems that the techdystopians have been warning about when AI starts to create — the black box can be too black for humans to understand. If they cannot understand the black box, how can they control it?22

If they cannot control it, then why should AI not be recognised as a third form of legal personality (in addition to natural and corporate personality)?

The third stage — Autonomous Artificial Intelligence (AAI)

Lucas de Lima Carvalho in his article Spiritus Ex Machina posits the idea that “AAI represents the third wave of the [AI] revolution”.23

For the purpose of encapsulating the “third wave”, AAI is defined as a system that is:

(i) is capable of performing tasks commonly associated with human intelligence and beyond, (ii) is not directly or indirectly controlled by human beings, and (iii) has full managerial power over its own actions and resources, which may be contained, but not controlled by human beings or by entities (legal or otherwise) representing the interests of human beings.24

Much of this will occur via disintermediated media such as the internet and indeed it may be quite hard to locate exactly where AAI resides — at this stage form a tac perspective but importantly also form a jurisdictional perspective.

Carvalho stresses that the AI defined here only reaches the level of limited Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI), and thus, “human containment should be theoretically possible”.25

However, Carvalho observes that “of course, one day, human beings or the AAI they have developed will create a form of ASI that cannot be limited or contained by human efforts (full ASI)”.26

The transition from the former to the latter is the focus of the third rule in Carvalho’s definition of AAI. He states that the:

. . . the third rule is crucially important for the digital economy, because it is designed for a transitional stage between a “human-led” digital economy to the era of technological singularity (an era in which it is believed that human beings will be subjects of full ASI, rather than controllers or even containers of its operations).27

The article devotes a chapter to the above definition for the purpose of arguing how the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s definition of AI:

. . . fails to address situations in which the digital compo- nent is not only the channel through which operations are carried out, or the product or service being traded by the relevant parties, but [it] is a feature of the parties themselves.28

Carvalho doubts that current law and policy:

. . . will be of much relevance when this form of ASI is capable of “thinking” and acting with a capacity and a precision millions of times more developed than those of the most brilliant human minds in history.29

The dystopian myths that pervade our minds when we think about this inevitable future pose many philosophical and legal questions. Nevertheless, in this moment, a time between the development of the law and policy, and the development of full ASI or technological singularity, to explore these questions and defy the myth that “science fiction writers foresee the inevitable, and although problems and catastrophes may be inevitable, solutions are not”.30

As Carvalho observes, perhaps the time in which humans leave the driving seat of the law and its systems to AAI and retire to passenger seat in hope of being subjects of benevolent intelligence is near,31 but that time is not now. Before this happens we can be prepared. We must ask these somewhat unnerving questions that provoke challenging unknowns and theoretical thinking. We must start sketching an empowering critique of technological existence.32

Conclusion

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”33

With AAI, machines (whether virtual or physical) are now approaching the stage where the uncanny valley disappears.

When a robot passes the Turing test,34 can it still be property? Can its creations still be property, and if so, of whom? What happens when robots and AI develop their own theory of mind?35 Does it pass into personhood,36 or quasi-personhood37 (such as a ship, which has separate legal personality for some matters)?38

If AAI can create to all intents and purposes independently of the original algorithm, can it own what it creates?39 If it can own what it creates, and Thaler is getting close to accepting that as a potential hypothesis, and at least not a hypothesis so obviously illogical as to be instantly dismissed, can the AAI itself have personality?

If the answer is yes, where does that personality inhere? The next question then is whether the uncanny valley has been bridged, and there is no difference between the AAI, however embodied, and a human,40 such that the AAI should have some rights inhering in humans (or at least the right not to be enslaved).41

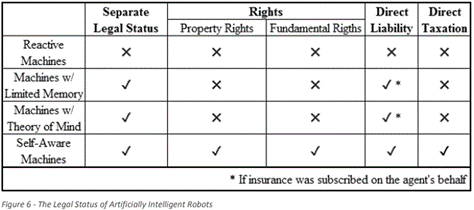

Maia Alexandre proposes a taxonomy of rights and liability:42

The answer is not obvious.

END NOTES

1. Thaler v Cmr of Patents (2021) 160 IPR 72; [2021] FCA 879; BC202106774.

2. See for example K Capek’s 1921 play RUR, which introduced the word “robot”; F M Alexandre The Legal Status of Artificially Intelligent Robots— Personhood, Taxation and Control (June 2017) ANR: 489792 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2985466; K Tranter, “Frankenstein Myth” in Living in Technical Legality: Science Fiction and Law as Technology, Edinburgh, 2018, at 27.

3. Lessig’s theory of code grasps towards this barrier — see T Blyth “A (Legal) View form a Bridge Over Troubled Waters: Metaphors for Information and its Value in the Information Age” (2000) 7(4) Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law 44 at [34].

4. E Karner, B Koch and M Geistfeld Comparative law study on civil liability for artificial intelligence, EU publications, European Commission, November 2020, p 23; F M Alexandre, above n 2, Ch 2.

5. Above n 1, at [5].

6. Above n 1, at [7].

7. Above.

8. Above n 1, at [15].

9. Above.

10. For example the South African patent office approach.

11. I Baucom, Specters of the Atlantic: Finance Capital, Slavery, and the Philosophy of History, Duke University Press, 2005, p 52: “the machine is going to take over”, but this is a good thing.

12. Above n 1, at [126].

13. D Nye, Technology matters: Questions to Live With, MIT Press, 2006, p 20–30; see also L Lessig, Code: And Other Laws of Cyberspace, Basic Books, 1999, discussed in Blyth, above n 3. Lessig’s concept is that the fundamental architecture of cyberspace is one that is inherently susceptible to regulation.

14. C Fredenburg “Commissioner of Patents challenges landmark ruling on artificial intelligence Lawyerly 30 August 2021 www.lawyerly.com.au/commissioner-of-patents-challenges-landmark-ruling-on-artificial-intelligence/; The Commissioner has since appealed the decision, alleging the “appeal does not represent a policy decision by the Australian Government on whether AI should or could ever be considered an inventor of a patent”. The Commissioner alleges that the appeal is a question of law and a public interest case. Interestingly, Dr Thaler’s patent application in the UK, the US and Europe have all recently been heard and rejected: M Bolza “Latest patent ruling rejecting AI inventorship puts Federal Court in minority” Lawyerly 24 September 2021 www.lawyerly.com.au/ latest-patent-ruling-rejecting-ai-inventorship-puts-federal-court-in-minority/.

15. F Wheelahan, S Reddy, D Fixler and P Keane “Patentability of AI-generated inventions in Australia” Corrs Chambers Westgarth 15 April 2021 www.corrs.com.au/insights/patentability-of-ai-generated-inventions-in-australia#_ftn1.

16. B2C2 Ltd v Quoine Pte Ltd [2019] SGHC(I) 3.

17. Quoine Pte Ltd v B2C2 Ltd [2020] SGCA(I) 02 at [150].

18. T A Smith “Tools, Oracles, Genies and Sovereigns: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Government” 7 May 2016 pp 19–20 https://ssrn.com/abstract=2637707.

19. Above n 17, at [159].

20. Above n 16, at [5].

21. Above n 17, at [114].

22. C Zednik Solving the Black Box Problem: A Normative Framework for Explainable Artificial Intelligence https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1903/1903.04361.pdf.

23. L Carvalho “Spiritus Ex Machina: Addressing the Unique BEPS Issues of Autonomous Artificial Intelligence by Using ‘Personality’ and ‘Residence’” 2019 47(5) INTERTAX 425.

24. Above, at 427.

25. Above n 23, at 431.

26. Above n 23, at 443.

27. Above n 23, at 433.

28. Above n 23, at 427.

29. Above n 23, at 443.

30. Above n 23, at 442, quoting I Asimov, Asimov on Science Fiction, Doubleday, 1981, p 61.

31. Above n 23, at 443.

32. K Tranter, above n 2, 2.

33. A C Clarke, Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible, Indigo, 1962.

34. C Gershenson “What Differs Us From Machines?” December 14, 2019 16946; T King, N Aggarwal, M Taddeo and L Floridi “Artificial Intelligence Crime: An Interdisciplinary Analysis of Foreseeable Threats and Solutions” (May 2018) https://ssrn.com/abstract=3183238.

35. M A Lemley and B Casey “Remedies for Robots” (2019) 86(5) University of Chicago Law Review 1311.

36. A Bertolini Artificial Intelligence and Civil Liability (July 2020) ss 2.1.1 and 2.1.2.

37. Nanos “A Roman Slavery Law: A Competent Answer of how to Deal With Strong Artificial Intelligence? Review of Robot Rights with View of Czech and German Constitutional Law and Law History” (2020) Charles University in Prague Faculty of Law Research Paper No 2020/III/3.

38. F M Alexandre, above n 2, Ch 3.2 and at p 19.

39. T Blyth, above n 3, at [75] to [82].

40. K Darling “Extending Legal Protection to Social Robots: The Effects of Anthropomorphism, Empathy, and Violent Behavior Towards Robotic Objects” (April 2012) Robot Law, Calo, Froomkin, Kerr eds, Edward Elgar 2016, We Robot Conference 2012, University of Miami https://ssrn.com/abstract=2044797.

41. J M Puaschunder “On Artificial Intelligence’s Razor’s Edge: On the Future of Democracy and Society in the Artificial Age” (December 2018) 2(1) Journal of Economics and Business 100 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3297348.

42. F M Alexandre, above n 2, at p 57.